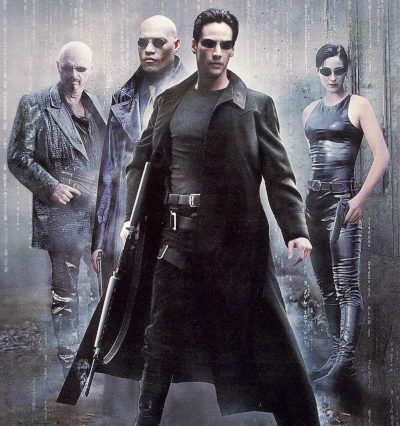

On the occasion of the 25th anniversary of The Matrix's release, a particular conundrum has been bothering me for a long time; like a splinter in my mind, driving me mad.

What is The Matrix? What is it really? What does it truly represent as a pop-cultural phenomenon?

I saw The Matrix during the first week of its original release in 1999. I was 21 years old, in between stints at college, and still living with my parents and working in a movie theater in Dallas, TX. My job made it possible for me to get free passes for my friends, and we all went together to see it. I feel like it's relevant to mention that I went and voted in a local election (and was stared at for an uncomfortably long period of time by a little girl who was there with her mother - like, shocked, gape-jawed staring - possibly due to the fact that I pulled up to that polling place looking like a Mallgoth who rolled right up out of a Hot Topic) before driving up to Bill's Records And Tapes on Spring Valley and Coit RD, and calling my friends from the payphone outside the nearby grocery store to arrange how we were going to meet up. Thinking about that now makes me smile, considering the role that payphones played in the first film.

The film blew my mind, as it did with so many others - just like the film Dark City had done a year before. I know people have made a ton of comparisons between the two films, that they share a lot of similarities and themes, and even some similar aesthetics. I know they were shot on some of the same sets. And I feel like both films informed a lot of my "subconscious programming" (if that makes sense) in the years that were to come.

I attended a showing of The Matrix Experience At The Cosm Theater recently, and it kicked ass.

For me, the first Matrix film is particularly evocative of a certain time and a place in my life, and a particular vibe that went along with it. That magical era in time that Gen Z calls "Y2K." For me, this also includes all of 1998-1999; because the "vibe" that The Matrix film expressed, the cultural zeitgeist, really had its heyday starting in 1998. Then it proceeded through 1999-2001 - right smack into the double whammy of the Dotcom Bust and the events of 9/11, when the world changed forever.

This time period is also excellently expressed in musical form in Massive Attack's album Mezzanine, which was released in 1998. One of the tracks on Mezzanine, "Dissolved Girl," appears in the first Matrix, over Neo's earphones as he naps at his desk right before getting the fateful message to follow the White Rabbit.

Mezzanine is considered by some to be a kind of "unofficial soundtrack" to The Matrix. It came out the same year. The album and the film just kind of go together. They have the same vibe. And one thing that Massive Attack fans have lamented since it dropped is that Massive Attack "never made another Mezzanine." They don't just mean another album that did as well. They're talking about that album's specific sound and atmosphere, which has not carried over to any of their subsequent albums.

Both the original Matrix film and the album Mezzanine are products of their time. They are uniquely, intrinsically, 1998-1999. I don't think they could be made in any other time, and I don't think that there's a specific "formula" that would enable the Wachowski Sisters or Massive Attack to just keep cranking out more of the same. But people seem to desperately want to recapture that time period. If they can't go back to that, they want to break off a piece of it to carry with them into their current day-to-day life. For people who were born after 1998, I think there is a feeling of wistful nostalgia for a time they never knew, a time before the wheels figuratively started to come off. But they started to come off almost immediately right after that.

It really does feel sometimes like people want to somehow shift the world into the timeline where 2001 and everything after happened differently, and we ended up facing the dystopia we were expecting to get - the one that our media seemed to be training us to resist, instead of the one we actually ended up getting. (Though, let's be fair: the corporate media "suits" were never going to just hand us the tools or language to resist them, either way.)

The sequels have been taken back out and re-examined in the years since they were released. I'm glad that the sequels seem to be finding their audience now, and I'm convinced it will eventually be the same with the fourth film. Which I want to address now, even if this essay is supposed to be about the first film. Spoiler warnings apply from this point forward.

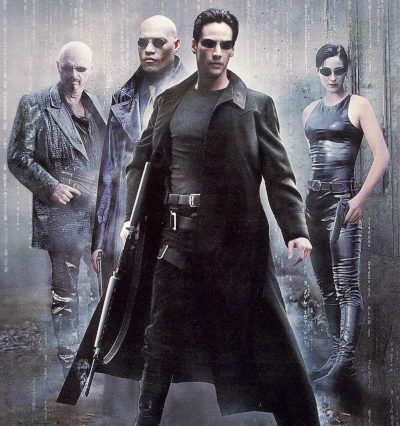

Obviously the importance of The Matrix and its sequels to the Transgender community cannot be overstated. And, before really I get into this: there are a certain number of people who were never going to take the fact that The Matrix was on some level a Transgender allegory very well, once they'd applied their own warped misunderstanding of the film into the mindset that would later become the basis for the "Men's Rights" or "Manosphere" movement. And, to be clear - it was never only *just* a Transgender allegory. That was just one level of it, or one aspect of it (though that aspect was definitely very there and very real, even back then; as Trans people and Queer people were aware.) But it was never meant to be a male chauvinist allegory. This should have been obvious from the text, but here we are.

The "manosphere" guys calling themselves "Redpills" loved The Matrix when they thought it was about an epic, prophetic, (seemingly white, heterosexual cis male) hero saving the day. But when the Wachowski Sisters came back with the sequels and said "wait, there's more to this story, the prophesy isn't what it seems to be," they lost their shit. Because in their minds, they were all Neo. They did not respond well to the way that the Sisters turned the ideas in the original film on their head; robbing Neo of his seemingly prophetic invincible immortality, and revealing deeper levels to the story that no longer fit or meshed with a lot of viewers' beliefs or identities in the process.

I mean, I know there were people who wanted an Actual Redpill, like it was a Hogwarts Letter. I know this on a personal basis. But in a sense, I think Neo-ism had low-key become a religion to some of these people before Lana and Lilly came out. And like a lot of people who get attached to a godform without really examining the reasons behind it, their "god" becomes a metaphor or stand-in for their own ego or residual self-image. And I think maybe the so-called "Redpills" are fighting for their idea of what "the Matrix was supposed to be," and are trying to "reclaim" a movie and its symbolset for what their idea of masculinity is - a movie created by two Transwomen, with Transgender themes. Which would mean that their attempts to "reclaim" it are just misappropriation. Yes, even if they feel like it was misappropriated or "stolen" from them.

(And yes, maybe some of them are stuggling with an existential crisis because they're struggling to conform to this very narrow, restrictive idea of "alpha male" masculinity; but at the same time, their egg is trying to crack...)

And when Lana Wachowski came back after 18 years(!!) with another installment of the Matrix Francise, the usual suspects wasted no time in "throwing their toys out of the pram" over it again. It didn't matter that her other stated reason (besides having to make the film or Warner Bros would do it without her) was the need to reach out to two fictional characters she created for comfort in a time of intense grief. No, according to the haters "it was a cynical cash grab," or "she made it suck on purpose so she could give Warner Brothers and her fans the finger" (and presumably get her phone call.) But examined thematically, it's a complete and total rejection of the idea that she and her sister should be obligated, by the studio or anyone else, to just crank out more of the same and rehash the same story beats (which would have actually been a cynical cash grab.) And the Extremely Mad Fans complained about this, too.

What Lana Wachowski ended up making was an emotionally sincere work of art. But those fans didn't really want an emotionally sincere work of art, they wanted feelgood escapism that they could disappear into during a time of crisis. And on one level, there's nothing wrong with this: it's a big reason why we go to the movies. And since Matrix Resurrections came out during the middle of a global pandemic, maybe folks could have been excused for wanting some feelgood escapism right about then. But one of the underlying themes of The Matrix - perhaps the underlying theme - is disconnecting oneself from false narratives or paradigms, and facing reality as it is.

But I think that when you get down to it, those so-called "Redpills" didn't want Lana to make another movie about her lived experience. They wanted her to make it about them.

There's also a scene within Matrix Resurrections that some folks have interpreted as poking fun at all of the fans who have devoted so much time and energy into analyzing these films and their meaning; namely, the scene of the game developers trying to work out why the original story (a video game trilogy in the context of the film's storyline) worked so well. And I don't really think this scene is meant to be an insult to the fans, as so many people seemed to think after seeing the fourth film. Instead, I think it is meant to maybe suggest that perhaps it's both futile and a little cynical of the Hollywood "Suits" (both within the context of the film's storyline, and in real life) to try and reverse-engineer something via focus group that began as a work of genuine artistic expression, in an attempt to duplicate the success of the original work.

"But..but..but the fight scenes and the effects in Resurrections were lame -" Let me stop you right there. I don't really think it's about the fight scenes or effects anymore. (Also, you're wrong. Maybe the fight scenes weren't quite up to par with the first three films, but anyone who didn't get emotional when they went to IO for the first time - or any time Neo and Trinity were able to just interact as themselves, re-united for the first time in literal decades, needs to fix their hearts IMHO.) I think it's about the emotional connections between the characters. Another point that "The Suits" were missing is that The Matrix was a love story. And that the sincere emotional bond between Neo and Trinity was the most powerful force of all, in the face of The Arcitect's inhumanly brutal efficiency, and the Analyst's snide cynicism.

And on another level, Resurrections seems to be about how a lot of us who latched onto the first film are now facing middle age having lived unfulfilled lives, and having compromised on realizing our dreams. At turn of the century, Generation X was strugging with the idea of "selling out" and "leading lives of quiet desperation," like Neo in his "before-life" as Thomas Anderson. Giving up on youthful, rebellious ideals, assimilating into the workforce, and becoming obedient, reactionary consumer-serfs like our parents had. No one in 1999 was aware that all of this would change in just a few years.

No, the anxiety that seemed to be gripping Generation X as we came of age was that, like the Boomers before us, we would settle for bland, materialistic lives of comfortable but tedious mediocrity instead of seeking any kind of real enlightenment or creative fulfillment. A lifestyle full of material comforts and financial security that was devoid of any actual spiritual growth or individual expression seemed like a horrifying dystopia to some: and this was the crisis that turned up again and again in the media of the time (Dark City, The Truman Show, Fight Club, etc.) We had no idea what form the dystopia would actually take when it came, or that even basic necessities would be beyond the reach of many of us when it happened.

After all, that was the social contract that the Executive or Billionaire class, the owners of the means of production, made with the middle/working class after the social upheaval of the 60s and 70s: "go back to work in the field, the office or the factory. Don't don't go looking for anything above or beyond that, and don't make any more waves. Conform, and a comfortable living will be assured. The only true freedom is the freedom to consume, and The Bad People want to take that away from you." But when our parents complied, they just played their trap card: Ronald Reagan, who worked on pulling that ladder all the way up. Now, the anxiety that a lot of people feel is not "will I live a fulfilled life if I participate in neoliberal capitalism?" but "will I die homeless under a bridge if I fail to successfully participate in neoliberal capitalism?" (unless you were born into poverty, or a marginalized out group: in which case, that was always the reality you were facing.)

Maybe some people didn't want a Matrix story about Neo and Trinity as tired, unfulfilled, middle-aged Gen Xers who gave up on living as their authentic selves - but that's the reality that a lot of us are living in. The real question is, how do we manage to live the lives we want, before it's too late? A lot of us have gathered that this probably isn't going to be very likely to happen without massive societal change. And a film from 1999 can give us the inspiration and the symbolism needed to encourage us, but nostalgia alone isn't going to get us there, and escapism definitely isn't going to get us there. As the saying goes, we have to be the change we want to see in the world.

But I think the real issue is that people loved The Matrix at the end of the 90s, when it was challenging the status quo at a time when Gen X's main concern was if we were going to compromise our dreams for a comfortable life and stability, like our parents had. The fandom backlash arose when it was still challenging the status quo post 9/11, when the continuity and stability of the status quo was all people seemed to want. And the fandom backlash is still, well, backlashing, up to the present day.

They miss the time before it "got political," and made them uncomfortable, and challenged their worldview. I miss the time, or a theoretical time, when evry aspect of it - philosophy, reality, sexuality - was on the table for discussion, and that's what made these movies so cool. I miss the days when the fact that these movies challenged the worldview of the viewer WAS THE WHOLE POINT.